A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly.

Specialization is for insects.

—Robert Heinlein, Time Enough for Love

Buddhist tantra is about elegant, accurate, kind, effective, expansive action in the real world. That means that it values skill, creativity, and accomplishment.

Tantra aims at mastery: mastery of specifically religious techniques, but also of all arts, sciences, and practical know-how.

Tantra engenders all-around cluefulness: savoir-faire, improvisatory panache, and practical élan.

Some specific methods of tantra develop mastery, but mostly it’s the power of the attitude. Tantra develops discipline, precision, commitment, and confidence. You need these general-purpose emotional skills to be competent at anything—or at everything.

Accomplishment is a natural outcome when you unclog energy. Then you free your passion—your caring about real-world specifics—for action. The ability to enjoy all circumstances cuts through complaints—the limiting ideas that something is wrong with the world or with yourself. Spacious passion produces spontaneity, grace, and pride without aggression. A tantrika needs nothing and has nothing to lose, so he or she is willing to take drastic action, without flinching, when needed.

Specific skills

In pre-modern Tibet, well-educated lamas had to master a university curriculum that covered all the intellectual disciplines known then: from astrology through botany, calligraphy, dance, history, medicine, poetry, psychology, and so on to zoology. (Well, maybe not zoology, but at least demonology, a branch of cryptozoology!) Of course, most of the specific content of Tibetan education was completely wrong. However, the attitude that you should learn as much as possible, about as many things as possible, remains valuable.

Westerners often have the idea that “spirituality” is the opposite of “worldly concerns.” They are surprised, baffled, and even annoyed when they see how much energy Tibetan teachers put into creating useful or beautiful things. “High lamas” turn out to be accomplished experts in unlikely disciplines like carpentry, target shooting, or film-making.

Tantra is anti-spiritual, though. It is mainly about “worldly concerns,” so this is no contradiction.

Elitism

At this point, you may be thinking tantra sounds elitist. You might not be good at everything; you might not even be particularly good at anything. A religion that is only for special people might sound unattractive, or even evil.

Remember, though, that we’re now in the result section of this outline of tantra. I’m writing about the goal, or the ideal.

Tantra has prerequisites; but being already accomplished is not one of them. Mastery is an aim, not a starting point.

Tantra requires hard work, however. It is expansive, but not laid-back.

Consensus Buddhism sometimes seems to promote itself as a religion for dropouts, space cadets, and victims. Tantra is incompatible with seeing yourself that way. If you are willing to let go of that kind of self-definition, it has methods for developing confidence and competence—but you need to leave ordinariness behind.

Tantra is, in fact, elitist—depending on what you mean by that word. It could be meritocratic. It could be open to anyone who meets the functional prerequisites, and is willing to follow the path.

Tantra can’t be made compatible with some extremist egalitarian ideologies, though. It’s just a fact that some people are better at some things than others. That has natural consequences. For example, someone who is better at a skill can often teach it to someone who is less good at it, and not vice versa.

Historically, tantra has almost always been elitist in a different sense. It has mainly been reserved for the ruling class, because practical mastery leads to power, and the ruling class wants to keep power for itself. Social, political, and economic elites have created artificial obstacles to keep commoners from practicing tantra.

Tibet, for example, has a hereditary caste system, not unlike India’s. Tibetans—like civilized people everywhere—are obsessed with social class distinctions. It would be unacceptable for a Tibetan aristocrat to be religiously inferior to someone from a lower caste. So it is important to keep low-caste people from religious accomplishment.

This is one reason Tibetan conservatives oppose teaching tantra to Westerners. It is not only racism; it is also classism, or casteism.

I’ll write much more about this in upcoming posts. It’s one key to understanding why Tibetan tantra is mostly useless in 2012.

The bridge builder

The epitome of tantric mastery was Thangtong Gyalpo (1385–1464).

He was a genius; a Tibetan Renaissance Man. For his religious accomplishment, he is generally regarded as a Buddha. He invented the iron-chain suspension bridge, which could span broad rivers for the first time, and built more than a hundred of them across the Tibetan region. He was the inventor of the art form known as “Tibetan opera,” and his operas are still frequently performed. He was an architectural innovator, building numerous temples of peculiar design, some of which I’ve visited. He was a painter, sculptor, doctor, composer, musician, and poet. I expect he cooked a mean momo.

Here’s an extract from a letter to my lamas, from when I was on pilgrimage in Bhutan in 2003:

As an MIT graduate I have a special place in my heart for Thangtong Gyalpo: he’s the only acknowledged Buddha who was also an engineer. (As far as I know.)

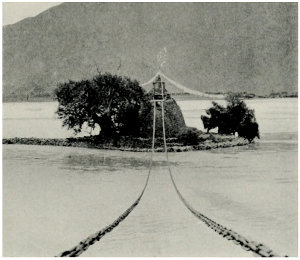

According to my guidebook, only one of his bridges is still functioning. I saw it today, and I think the book was exaggerating. It is no longer functioning, and on the whole is no longer functional. Unfortunately, since the building of a modern Bailey bridge across the same gorge in 1978, it is no longer used, has not been maintained, and is rapidly falling apart; which is very sad.

It’s a damn fine piece of engineering. It’s about seventy-five feet long, with nine chains hung to give a U-shaped cross-section. The chains are anchored in stone gatehouses at either end. The roofs of these have been allowed to collapse, so now water runs through them and the masonry is also collapsing. Unless some reconstruction is done, I think the chains will fall into the river within a decade.

The chains themselves are in perfect condition. They show very little rust, and look like they could have been forged a year ago. Apparently he used an alloy that is both strong and rust-proof. Although my engineering training was entirely un-civil, it looks to my eye like the bridge was substantially over-engineered, which is probably why it has survived six hundred years. (His bridge over the Tsangpo must have been several-fold longer; I speculate that he used the same gauge chain on all his bridges, which made for overkill on this one.)

The cross-members have all fallen away, and the chains are now tied to each other instead with baling wire, which is also rusting away, so they hang free in many places.

One could, however, still walk across; and having in this case more devotion than sense, I set out to do just that. I was about a quarter of the way across before Norbu, the translator, noticed and yelled at me to come back.

Obviously these bridges were great things. I asked Norbu why people hadn’t built more of them after Thangtong Gyalpo left. I had to ask three times in different ways before he understood, because it was such a stupid question. “They couldn’t,” he finally replied. “He built it with his miracle power, you know.”

This is why I hate miracles: they are such an obstacle to people using their own gumption and applying methods: whether methods of civil engineering or meditation.

Tragically, the bridge was completely destroyed a year later.