For a hundred years, the West has wrestled with the problem of ethical nihilism. God’s commands once provided a firm foundation for morality; but then he died. All attempts to find an alternative foundation have failed. Why, then, should we be moral? How can we be sure what is moral? No one has satisfactory answers, despite many ingenious attempts by brilliant philosophers.

Buddhism has wrestled with the same problem for much longer: most of two thousand years. According to Mahayana, everything is empty. This means everything exists only as an illusion, or arbitrary human convention. “Everything” must include śīla—codes of religious discipline. (Those are the closest thing Buddhism has to morality.) “Everything” definitely includes people, the main topic of ethics.

For two millennia, authorities have acknowledged an apparent contradiction: why should we conform to śīla if it is empty, illusory, arbitrary, or mere convention? If people don’t really exist, why should we have ethical concern for them? Numerous ingenious answers have been proposed by brilliant philosophers. No one answer has been broadly accepted, which suggests none is satisfactory. Buddhists have argued endlessly, sometimes bitterly, about this problem; this continues in the contemporary West.

In this post, I will suggest that the problem lies in the Mahayana treatment of emptiness and form. Vajrayana offers a different understanding of what emptiness is and how it relates to form. In Dzogchen, this provides an alternative approach to beneficent activity. This approach seems strikingly similar to that proposed by the psychologist Robert Kegan, whose developmental ethics model and its application to Buddhism I discussed recently. I suggest that Dzogchen and Kegan’s work each cast light on the other, and together they may dissolve the foundations problem in both Western and Buddhist moral philosophy.

The Moonpath to Elsweyr

The attempted solutions from Mahayana apply versions of the “two truths” doctrine. (I will use “Mahayana” in the narrow sense, as excluding Vajrayana.) There is the absolute truth, that everything is empty, without true existence; and the conventional truth, that forms exist more-or-less as they appear. Since both truths are true, these cannot conflict.

But how can that be? There are many different, complex and difficult explanations for this. Mahayana philosophers disagree sharply about which is correct—which is evidence that none are. Most agree that only Buddhas are capable of fully apprehending the relationship between the two truths, which comes close to an admission that they actually can’t be reconciled.

In fact, I think that none of the explanations works. Explaining how and why each is wrong would be a huge project, so I’m not even going to start on that here! However, Moonpaths: Emptiness and Ethics, an impressive book on this topic, was published just last month. It is entirely about this problem, which shows that the authors consider the problem unresolved—or at least had not been resolved before now! And, indeed, despite numerous statements of collegiality, they seem not to have come to a shared conclusion.

Moonpaths, written by “The Cowherds,” an all-star team of heavy hitters in Buddhist and Western philosophy, is probably the most sophisticated book that has ever been written on Buddhist ethics. It is also—it seems to me—a complete dead end.1

The overall problem, I believe, is that Mahayana metaphysics in practice separates form and emptiness into distinct realms. There is the perfectly solid actual world of form, and the perfectly inaccessible Faerie Neverland Nirvana of emptiness. This makes emptiness invisible and enlightenment impossible. The scriptural path to emptiness is naught but a mirage, a myth, a moondream.

Since emptiness is always elsweyr, śīla becomes completely definite. Since emptiness has been snatched away, morality turns into rigid forms.

In fact, it is more-or-less explicit in some versions that this is the reason for keeping form and emptiness separate.2 If emptiness leaked into conventional reality from Fairyland, it would corrode śīla. Still worse, it would threaten the feudal-theocratic social order, which was justified in terms of conventional morality. That made it politically imperative to put emptiness out of reach. Thus it was primarily the threat of ethical nihilism (or even ethical flexibility) that motivated Mahayana scrupulosity concerning theories of emptiness that risk ontological nihilism (or even ontological flexibility).

I said above that Mahayana separates form and emptiness “in practice,” because the scriptures often say otherwise. The heart of the Heart Sutra is “form is no other than emptiness; emptiness is no other than form.” Mahayana sects acknowledge that this is true in theory, but find ways to deny its practical relevance. They say that form and emptiness are unified in Neverland (the metaphysical fantasy of ultimate reality, Elsweyr), but emptiness cannot be found by ordinary people in the ordinary world. That is reserved for imaginary Buddhas.

Everyday emptiness and ethics

I think of Vajrayana—especially Dzogchen—as calling Mahayana’s bluff. It puts into practice concepts Mahayana considers true only “ultimately” and theoretically. Vajrayana treats them as workable everyday realities—not abstract, incomprehensible holy mysteries.

Whereas emptiness is the nearly-impossible goal of Mahayana, it is the taken-for-granted starting-point of Vajrayana. Tantric practices, such as yidam, work with vivid empty form as an intrinsic quality of everyday being. Because emptiness is an everyday experiential reality, inseparable from form, its conceptual presentation is rather different than in Mahayana. Emptiness is luminous (ösel), radiant, full of dynamic potential (tsal); not a mere “non-affirming negation.”

“Non-affirming negation” is the summary slogan of Prasangika, the Mahayana metaphysics promoted by the Geluk School of Tibet. “Emptiness,” for Prasangika, is nothing more than the denial of true existence. That leaves “conventional” existence—particularly śīla and authority—untouched. Prasangika was the Geluk rhetorical strategy for keeping emptiness and form separate, and thereby justifying their theocratic rule, which was legitimated in terms of their supposedly exceptionally rigid adherence to śīla.

The Rangjung Yeshe Dictionary says of ösel:

A key term in Vajrayana philosophy signifying a departure from Mahayana’s over-emphasis on emptiness which can lead to nihilism. According to Mipham Rinpoche, ‘luminosity’ means ‘free from the darkness of unknowing and endowed with the ability to cognize.’”

Tsal has a range of meanings including radiance, skill, power, play, creativity, and dynamic potential energy. These may seem to be form qualities more than emptiness ones—but in Vajrayana those are inseparable!

In my discussion of Kegan’s model of ethical development, I wrote:

Stage 5 recognizes that [ethics] are both nebulous (intangible, interpenetrating, transient, amorphous, and ambiguous) and patterned (reliable, distinct, enduring, clear, and definite). Nebulosity and pattern are inherent in all systems, and are therefore inseparable.

I believe this is faithful to Kegan’s scheme, but the presentation is straight-up Tantric. “Nebulosity and pattern” are more-or-less emptiness and form, as they are understood in Vajrayana. The ten qualities I enumerated correspond to the ten Tantric Buddhas. The five female Buddhas each have their specific emptiness-recognizing wisdom, and the five male Buddhas each have their specific form-wielding method. The Buddhas appear as five couples, each in sexual union, representing the inseparability of their corresponding qualities. So moral considerations are intangible yet reliable; interpenetrating yet distinct; transient yet enduring; amorphous yet clear; ambiguous yet definite. Each of these is obviously, unavoidably true, to some degree, in some sense, in at least some cases.

Dzogchen goes a step further than Tantra: it rejects the “two truths” concept explicitly. For Dzogchen, emptiness and form cannot be separated at all. They do not describe distinct domains or levels of existence. There is only one world, in which emptiness and form are both pervasive and obvious aspects of the dynamic play of phenomena.

Here’s Jigmé Lingpa’s take:

Apparent and ultimate are not found in awakening mind. To say “it is not” does not make it empty. To maintain “it is” does not make it solid.

Ken McLeod’s commentary on that:

On the one hand, when we see through the confusion of life, we know viscerally the utter groundlessness of experience. On the other, we are awed to the point of overwhelm at the fullness of life. There is no way to put into words this dichotomy that is not a dichotomy. These two aspects of awakening mind, in the hands of both practitioners and philosophers, evolved and calcified into the concept of the two truths: what is ultimately true and what is apparently true (often also translated as absolute truth and relative truth). Jigmé Lingpa, however, is not fooled by such conceptual formulations. In this line he points out that in the actual experience of awakening mind, ideas such as apparent and ultimate truth do not arise at all. They are conceptual designations, nothing more.

McLeod writes that, according to Dzogchen, the two truths philosophy “does not work”: “it has no power. We have lost our original path and now wander along the pathways of the intellect, adding argument to argument, constructing sophisticated lines of reasoning that go nowhere.”3

The Kunjé Gyalpo, the earliest major Dzogchen scripture, goes through all the Buddhist ethical theories, each of the codes of śīla, and points out what’s wrong with them. Each is based on some limited, fixed idea. Dzogchen comprehensively rejects fixed ideas. Not ideas—just their fixation.

Here Dzogchen bites the bullet, where Mahayana obfuscates. Emptiness does mean that no ethical system can work. However, “emptiness” does not mean “non-existence.” Morality is unavoidably intangible, fluid, transient, amorphous, and ambiguous. It cannot be captured by rules, principles, or lists of virtues. But this is not ethical nihilism. The activity of the Dzogchen practitioner is spontaneously beneficent.

This insistence that morality is empty, and so cannot be captured by an ethical system, but also has form, and so is meaningful and important, gets reiterated in many later Dzogchen texts. However, as far as I know, none of them have much more to say. There are hundreds of volumes of them, so it’s possible there’s an extended discussion somewhere. (If you know of one, I’d love to hear about it!) But I suspect not. Buddhism overall has little interest in ethics, and Dzogchen usually has much less to say about any topic than any other branch of Buddhism does.

The view that ethics can have no foundation, but is nonetheless compelling, seems obvious to me. Nietzsche pointed it out more than a century ago. However, Western moral philosophers have done naught since but form hostile tribes who argue that their pathetic attempt at foundation-building is less implausible than the others. “Well, at least utilitarianism could in principle tell you what to do—even though we can never apply it in practice—whereas virtue ethics never could give any specific advice even in theory!”

After Nietzsche, there are only a handful of works in Western moral philosophy that acknowledge both the emptiness and form of ethics. The clearest example is Will Buckingham’s Finding Our Sea-Legs, which I recommend highly. Two others are Simone de Beauvoir’s The Ethics of Ambiguity and Hans-Georg Moeller’s The Moral Fool. (Buckingham and Moeller both were influenced by Buddhism.)

Beyond method

So if ethics can have no foundation, if there are no absolute rules, how can we act morally?

Dzogchen, uniquely among Buddhisms, explicitly has no system of practice, and no overall principle or method. There is no defined path. This is a pervasive feature of the yana, not just its approach to ethics.

Two key Dzogchen terms are kadag and lhundrup. “Kadag” means “primordial purity.” There is no purity or impurity in reality. On recognizing this, the Dzogchen practitioner goes “beyond good and evil”—the same phrase Nietzsche used—and is freed from the grip of karma.

“Lhundrup” is spontaneous beneficent activity. Kadag and lhundrup correspond roughly with emptiness and form (in Mahayana) and with wisdom and method (in Tantrayana). But there is no set form or method to lhundrup. That’s why it is “spontaneous.”

Stage 5 of Robert Kegan’s developmental ethics seems to me startlingly resonant with Dzogchen—although he was not influenced by any sort of Buddhism, so far as I know.4 I wrote a summary of Kegan’s model recently; the remainder of this page assumes understanding of that.

Since they cannot be separated, kadag is the emptiness aspect of lhundrup; and lhundrup is the form aspect of kadag. What does that mean?

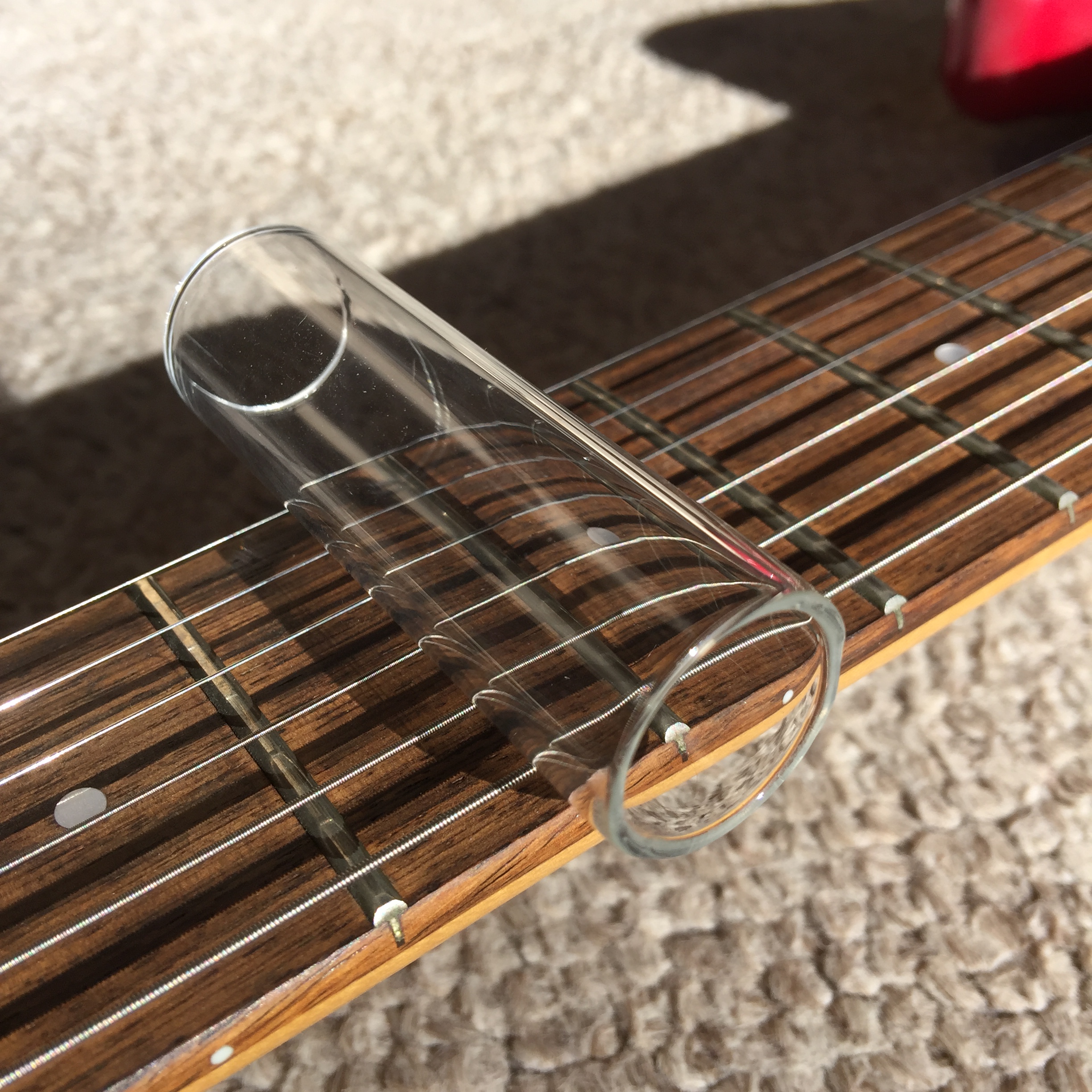

Kegan explains stage 5 in terms of a glass tube, such as a guitar slide.5 It has two openings. The “openings” do not exist without the tube. They are not any thing; they are empty space. Their boundaries are inherently ill-defined: how far does an opening extend inside or outside the tube? Yet a tube also cannot exist without openings; a glass cylinder lacking them is not a tube, it is a rod.

Without a view of primordial purity (the empty openings, which are undefined but which define a piece of glass as a tube) there can be no spontaneous beneficent action. Without spontaneous beneficent action (the glass tube, which has manifest properties) there can be no primordial purity beyond good and evil.

So far, this may all sound like complete gibberish. Or, it may sound paradoxical and contradictory. It is reasonable to be skeptical. Stage 5, and kadag/lhundrup, explicitly cannot be made sense of according to any system. Spontaneous beneficence cannot be judged as correct according to any fixed criteria. Here at stage 5, criteria, systems, principles, and rationality are objects, not the subject.

So how does this work, if not according to a rational system? Lhundrup is described as “natural” and “uncontrived.” Ethically accurate activity occurs spontaneously because we humans just are ethical. According to Dzogchen theory, this is an inherent aspect of the mind itself. This might sound unhelpfully like monist woo, or a dormitive principle that explains nothing.

So let’s take “natural” seriously and talk evolution. Humans are naturally ethical because we are social animals. Our brains evolved to do ethics. (There’s been extensive, fascinating research on this in the past decade.) Cultures evolve, too. Ones with more sophisticated ethics have out-competed and displaced those with less sophisticated ones. In modernity, we have elaborate institutions—based on stage 4 systematic ethics—which make societies of hundreds of millions of people functional. All this just happened. Even the construction of rational, stage 4 ethical systems just happened, as a natural process. There is no ultimate justification for evolution, and no ultimate justification for ethics. It’s just what we do.

However, it is not arbitrary: other social animals evolved basic morality independently, because it’s effective at organizing clans and team activity. It is not meaningless, and we can do it well or badly. As an evolved function of material brains and material culture, we do not do ethics by formless, ineffable intuition. There are moral specifics.6

Dzogchen has no fixed method; it is inherently improvisational, in all aspects, not just ethics. However, it deploys methods when, and if, they are useful. What methods? It has some of its own; but it also happily uses whatever tools are ready to hand. The Kunjé Gyalpo details the limitations of the methods of Sutra and Tantra, but it also recommends deploying them when they are helpful. Sutra and Tantra take their methods as Ultimate Truths; Dzogchen re-appropriates them as heuristics, ways-of-looking, tricks of the trade.

Tantra develops mastery of precise action within systems. For Dzogchen, systems are fluid and transparent. Dzogchen may use systems, or pieces of systems, in the flow of effortless improvisation. Where the tantrika is a technician, the Dzogchenpa is a musician. Great jam band players master the technical details of a musical genre, or many genres, but transcend them. They may reference, borrow from, combine, and play with styles and techniques, but their music flows spontaneously from the texture of the moment of playing.7

This is also the stage 5 approach to ethics. Stage 5 comes into its own when no ethical system has an adequate answer, yet action is required. Its improvisation follows no rules, but is responsive to the specifics of the situation. Typically it coordinates ethical considerations taken from multiple, incommensurable stage 4 systems, plus stage 3 communities and stage 2 interests.

From the point of view of the lower yanas, Dzogchen looks like magic. From the point of view of earlier ethical stages, a stage 5 solution can seem that way too.

Abandoning an attempt at an application

I hope some readers will have found this “explanation” exciting and illuminating; but I fear most will find it exasperating and incomprehensible. It has certainly been absurdly abstract.

This page was supposed to include an example, here at the end. I do not know of any detailed discussion of Dzogchen ethics; and I think Kegan’s few examples of stage 5 ethical practice are not concrete or compelling enough to replicate here.

So I started working through a particular ethical issue myself, looking at it from stage 3, 4, and 5 viewpoints; analyzing it in terms of the tantric five wisdoms; and observing the inseparable emptiness and form of the issues. My example concerned the UK leftist/Islamist alliance. That was a “hot topic” when I was working on it a month ago. After the Paris attack a couple weeks later, it is way too hot to handle. Points about how one does ethics would be overwhelmed by intense opinions about the meaning of the event.

So a different example would be good; but I don’t have time for one now. (Sorry!)

I do intend to develop this approach further, to make it more concrete, accessible, and actionable. That will be a big job. I will do it on a different web site, the Meaningness book site.

- Significantly, Moonpaths takes an exclusively Mahayana view. The Cowherds do not mention any Vajrayana (Tantric or Dzogchen) approach to its problem of emptiness and ethics. ↩

- See for instance Elizabeth Napper, Dependent-Arising and Emptiness, pp. 110, 148-150, 191-2, concerning Tsongkhapa’s interpretation. ↩

- This is in his excellent A Trackless Path, perhaps the most accessible Dzogchen book ever written. I will post a review of it next week. I chose it for its simplicity of language; many Dzogchen scriptures and major traditional commentaries also include an explicit rejection of the two truths. ↩

- Kegan almost completely ignores moral philosophy, although he certainly knows it well. His field is empirical psychology, not philosophy; but his model seems to me to address, and perhaps even answer, the fundamental problem of moral philosophy—ethical nihilism—which philosophy has almost completely failed to take seriously. Philosophers waste their time playing academic status games, elaborating details of approaches they know a priori could not work. ↩

- In over our heads: The mental demands of modern life, pp. 313 and 316. ↩

- Having realized that morality is an evolved, natural function, it’s also important to recognize that “natural” does not always imply “ethically correct.” ↩

- Sainkho Namtchylak, who sings in the video above, is Tuvan, from a culture that combines Mongolian Vajrayana Buddhist and Siberian shamanic influences. She trained in Western classical voice technique at university, while clandestinely becoming the first woman to master Khöömei, Tuvan overtone singing, traditionally a male-only style. She moved to Europe, and to avant-garde free improvisation, often with jazz and electronic instruments and styles mixed with Tuvan ones. My thanks to Beth Preston for introducing me to her music. ↩