I ain’t against gods and goddesses, in their place. But they’ve got to be the ones we make ourselves. Then we can take ’em to bits for the parts when we don’t need ’em anymore, see?

—Granny Weatherwax, in Lords and Ladies

Gods drive most people away from Vajrayana Buddhism before they even know what it’s about. That’s a pity, because it is not about gods.

As an atheist, I rejected Vajrayana for several years when I was told that it’s mostly about gods and demons and magic and stuff.

But Vajrayana (Buddhist tantra) doesn’t need gods anymore. We could take them to bits for parts, if we wanted; or just shoo them back home.

Or, better, we can agree to a new arrangement with them: we will treat them with the respect they deserve, if they stop pretending to exist.

“BUT!” you object, if you know anything about Vajrayana, “what about deity yoga?”

“Deity yoga” is perhaps the most important tantric practice. It requires the cooperation of “yidams,” who are…

Yidams are not gods

The textbook definition begins: “A yidam is a species of Buddhist god.” A page or two later, you read: “Not all yidams are gods; some are flesh-and-blood humans from history.”

You ought to be: Wait, wait—what what what what what?

It’s like reading a Wikipedia article that begins “A poguna is a species of Polynesian turtle…” and then the third paragraph says “not all pogunas are turtles; some are sea shells, or carved from wood.”

With that, you realize that to know what a poguna is, you need to understand their function: how people use them and why. It might be that turtles make convenient pogunas, especially in Polynesia, but being a turtle must be mostly irrelevant to the concept. Turtles and carved wooden knick-knacks are fundamentally different kinds of things. Maybe in America we’d use a plastic bowl for the same purpose.

Gods and dead people are fundamentally different kinds of things; so if both can be yidams, being a god is basically irrelevant.

It turns out that, for traditional Asians, gods made good yidams, but maybe in America something else works better.

What a yidam is

A yidam is someone you can consistently consider enlightened. In “deity yoga,” you relate to that person in particular ways. You “become” the yidam in meditation by visualizing yourself in their form, and by replacing your ordinary mind with their enlightened mind. Later, I’ll suggest ways to think about this operation naturalistically.

For this mind-meld to bring about your own enlightenment, you have to be confident that the yidam is already enlightened. Traditional Buddhists find it easy to believe gods are enlightened—easier than to believe in enlightened humans. So gods make good yidams for them. For Westerners who don’t believe gods even exist, it may be difficult to be confident they are enlightened.

There’s another problem. If the many yidams are gods, they form a polytheistic pantheon. Modern people mostly recoil from polytheism. There’s a left-over Biblical taboo against that, which persists even for many agnostics and atheists.

So, nowadays, it might be more effective to use non-gods as yidams.

Undivine yidams

All sorts of people, other than gods, have functioned as yidams.

Westerners may find it easier to take historical, human figures as yidams. For instance, Machig Labdrön was a Tibetan woman who lived about a thousand years ago.1 She is widely practiced as a yidam. Many Westerners find her inspiring and appealing.

In the Karma Kagyu branch of Tibetan Buddhism, the Karmapa—the human head of the lineage—is commonly taken as a yidam. Typically, his previous incarnations are visualized, but according to theory, those are more-or-less the same person as the one alive now.2

If you are confident that a living person is enlightened, they might make a good yidam—although this is atypical and has some obvious possible pitfalls. Living people may not live up to what you think “enlightened” ought to mean.

Ideally, you might use yourself! If you could convincingly visualize yourself as enlightened, you’d be enlightened—or else psychotic. (The user manual has one of those exclamation-mark-in-a-triangle-road-sign icons here.) Mostly, it’s difficult to to experience yourself as enlightened, so you experience yourself as someone else being enlightened, which turns out to be easier. That’s why yidam practice—or “deity yoga”—works!

Besides gods, dead humans, and fictional humans, all sorts of monsters, demons, and miscellaneous spooks also function as yidams.

The fact that these people are all either imaginary or decomposed is a non-problem. You don’t have to “believe in” someone to practice them as a yidam. Existence is irrelevant to the job.

Non-existence is not a defect

“That girl’s got a bit of natural talent,” said Nanny Ogg. “The rest of ’em are just along for the excitement. Playing at witches. You know, ooh-jar boards and cards and wearing black lace gloves with no fingers to ’em and paddlin’ with the occult.”

“I don’t hold with paddlin’ with the occult,” said Granny Weatherwax firmly. “Once you start paddlin’ with the occult you start believing in spirits, and when you start believing in spirits you start believing in demons, and then before you know where you are you’re believing in gods. And then you’re in trouble.”

“But all them things exist,” said Nanny Ogg.

“That’s no call to go around believing in them. It only encourages ’em.”

Yaweh apparently began life as one of the seventy sons of Asherah. Asherah was the wife of El, the king of the vast Israeli pantheon. Little Yaweh grew up to be the most aggressive of her children, renowned for his prowess on the battlefield.

The priests of Yahweh began their drive for domination by having their god take his own mother as his wife. Having displaced his father, Yaweh—according to these priests—became the most powerful of the gods. So if you wanted divine favor, you’d better give gifts to them, not to the priests of Baal, who was Yahweh’s older brother and main rival. Eventually, the Yahwite priests routed the followers of Baal, and of all the other gods.

Then, to salt the earth, they came up with a radical new metaphysical idea. The gods of the other priests were not just wicked and weak—the standard claim of rivalrous priesthoods since organized polytheism began. The other gods didn’t even exist.

Western culture has been obsessed with fighting over what does or doesn’t exist ever since.

This peculiar obsession is shared by Buddhism.3 According to Mahayana texts, nothing exists. At least, “not in some sense”—although exactly which sense has been hotly contested for millennia.

One remarkable feature of the “existence” concept is that essentially no one—in either the Buddhist or Western traditions—even tries to explain what it is supposed to mean. It’s assumed that everyone knows—but no one can say. The harder you look into it, the less coherent and consequential the idea becomes. (I plan to write about this at length someday; there’s a stub version here.)

Be that as it may, many Tantric Buddhist texts particularly emphasize the non-existence of the yidams. The aim of Vajrayana is to actualize the understanding that emptiness and form are inseparable. “Emptiness” is more-or-less “non-existence” according to some Buddhist philosophical schools, so yidams’ non-existence is particularly salient. Vajrayana practice manuals often warn against the error of imagining that you can turn yourself into a concrete, actually-existing god.

So… instead of quibbling over metaphysical technicalities, let’s grant that most yidams are mythical.

Westerners mostly reject myths. Christianity and Science4 both denounce them as false.

“False” is a bizarre, irrelevant objection, though. A myth is a religious fiction, and the yidams are fictional characters. Fictions are “false,” but no one objects to them.

Well, no one except philosophers. They debate the “Paradox of Fiction”:

- When watching a movie, or reading a novel, you may have strong emotional reactions to events, and care deeply about what happens to the characters.

- For something to matter, it has to exist. Imaginary events have no real value, positive or negative. Rationally, you should only have emotions about things that matter and have value.

- You know for sure that fictional characters don’t exist, and that fictional events didn’t happen and never will.

From this, it follows that you are “irrational, incoherent, and inconsistent,” and need a brain transplant.

Well, someone does… maybe it’s philosophers. This argument is obviously stupid.

Fundamentalists have another stupid objection. Some extremists oppose all fiction, because it is untrue and entertaining.5 Others oppose fantasy fiction specifically: the Bible should have a monopoly on supernatural tales, because other gods, spooks, and miracles don’t exist. Reading Harry Potter is the highway to hell.

Myths have great value, which has nothing to do with their literal “truth.” I have suggested that mythopoesis—the creation of explicitly “false” religious fictions—is the best strategy for naturalizing tantra.

(Supposedly I will write much more about that someday. If you believe my outline… but it is is a pack of lies. In the mean time, “Lies in which not everything is false” is a fine essay on Buddhist myths by Will Buckingham, an outstanding philosopher and my favorite ex-Buddhist myth-inspired fantasy fiction writer.)

We all do relate to fictional characters. They are important to us. Fiction is a powerful source of inspiration and insight. Asking “What would Aragorn do? What would Princess Leia do?” might be an excellent way to live. The same goes double for religious fiction: myths.

Once you realize being a god is irrelevant to being a yidam, and that existence and non-existence are irrelevant, and that the supernatural is as harmless in myths as in other fictions—then taking a god as a yidam is unproblematic.

But if it really bothers you, unquestionably existent (albeit dead) humans are also available, and can also do the job.

Enlightenment and other aims

Traditionally, yidam practice aims at “enlightenment,” which is why the yidams have to be enlightened. You visualize yourself as a yidam; that merges your mind with the yidam’s; then you are enlightened too.

You could probably visualize yourself in the form of the Stay-Puft® Marshmallow Man. You could recite the Stay-Puft mantra (“Stays Puft, Even When Toasted”™). This would be pointless, however. Presumably, you don’t believe he’s enlightened.

If you can’t see anyone as enlightened, there’s a problem. You may doubt whether that is possible, even in principle. Is there even such a thing as enlightenment?

I think such doubts are reasonable. Every little branch of Buddhism has its own story about what “enlightenment” means. They are drastically different, and most are obviously impossible or undesirable. Some other conceptions of enlightenment may be useful for particular purposes. I think we’d do better to give those more specific names, and ask hard questions about “what is this thing? is it actually achievable? what is it good for?” (I wrote about this in “Epistemology and enlightenment.”) If you share these qualms, it may be better to ignore “enlightenment.”

Instead, in yidam practice, and in tantra generally, we might aim at developing capacities, adopting stances, and engaging in activities.6 “Enlightenment” is a vague, uniform, singular goal; but capacities, stances, and activities are specific, diverse, and plural.

There are thousands of yidams—wildly different, vividly specific—who help you develop and master their particular capacities, stances, and activities. In consultation with your teacher, you can choose which yidam (or yidams) to practice, depending on what direction you want to head in.

Process and preview

I wrote this post several years ago. It was meant to be the first in a series explaining a naturalized approach to yidam practice. That was to be part of the series on naturalizing Buddhist tantra, which was part of the series on modern Buddhist tantra, which was part of this site’s general project of reinventing Buddhism for contemporary cultural, social, and psychological conditions. I abandoned all parts of that, with regret, long ago; but I’ve noticed this post was mostly done, and thought I might as well polish and publish it.

According to the outline, the pages in this section were to be:

- Yidam—A godless approach, naturally! [i.e., this post]

- Yidams are not archetypes

- Do we need Western yidams?

- How yidam practice works

- Body maps, yidam, and tsa lung

It’s likely I’ll never post the rest, so here’s a quick summary.

Yidams are not archetypes

“Yidams are not gods but archetypes” is a common, well-intentioned claim, but it’s inaccurate, and I think mostly misleading and unhelpful.

It’s an example of the psychologization strategy for naturalizing Buddhism. That turns external, supernatural entities into internal, psychological ones. The problem is that meaning is neither objective nor subjective, and yidams are neither independently-existing people, nor mental structures found “deeply within” yourself.

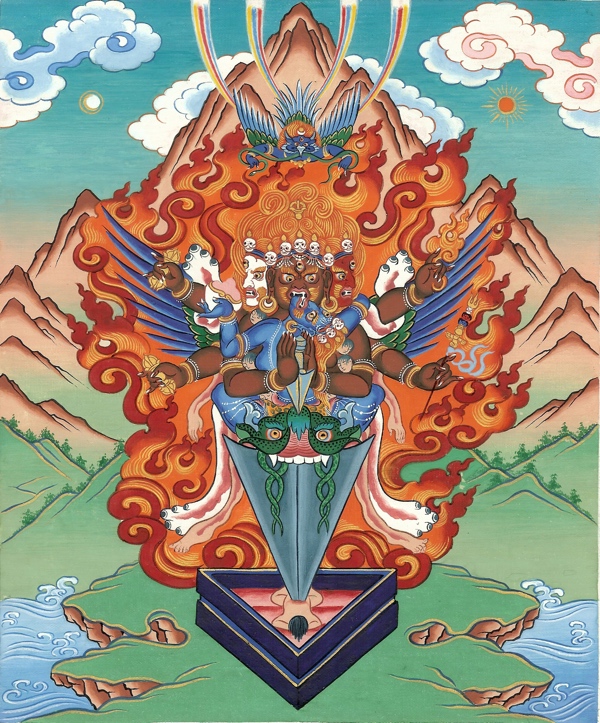

Archetypes are supposedly abstract, general, and universal. Yidams are extremely specific. Vajrakila—the yidam shown above—has three heads, six arms,7 wings, and no legs. Instead, his torso is fused at the waist to a huge three-bladed dagger.

Vajrakila is not universal. You will not find him “deeply within” yourself. When you “look within,” usually all you find are idle fantasies and stale emotional loops. The Protestant, Romantic-Idealist, and Jungian idea that Truth is found “deeply within” is antithetical to Vajrayana, which is about patterns of interaction, not psychology.

Vajrakila is also not an arbitrary cultural creation. He has an extremely specific form, and you aren’t to mess with it. Every detail has a particular significance, symbolism, and function, which weren’t just made up.

Those specifics are utterly bizarre. Westerners, when beginning with Vajrayana, often complain that they “can’t relate” to these “alien” yidams, and want ones that would seem more familiar. We should adopt existing deities from Western mythoi, they say. Athena, or the Virgin Mary, for example.

Do we need Western yidams?

Probably not. The idea is based on basic misunderstandings about the function of yidams.

I expect yidams that reference aspects of Western culture are possible—but I doubt they are necessary. And incorporating Western deities without incorporating Western religious attitudes, inimical to Vajrayana, seems difficult and maybe impossible.

Being Vajrakila is equally “alien” to all human beings. Tibetans don’t have three heads any more than Americans do. Initial familiarity with his image might give them a small edge during the first few hours of the thousands it takes to gain some proficiency as Vajrakila. BFD.

Being willing to deal with weirdness is part of what Vajrayana is about. You might as well start with the yidam as anywhere else.

Anyway, “starter yidams” are straightforwardly human, and as natural for Westerners as Tibetans. Yeshé Tsogyal is my main yidam. She’s “alien” only in being a teenage girl—and that has its own value.

More significant is that she’s enlightened, and I mostly don’t think of myself as being so. Enlightenment is alien to samsara—but it is natural for human beings.

Where there are humans,

You’ll find flies,

And Buddhas.

—Issa

Naturalistic yidam practice: how it works

This post would be an experiential—not mechanistic—account of “how it works,” in a naturalistic framework.

It would explain what yidam practice is like, and how to go about it, if you “don’t believe they exist.”

Body maps, yidam, and tsa lung

This post would speculate about how and why yidam practice works mechanistically, in terms of neuroscience and stuff.

I suspect tsa lung (“energy practice”) shares some of the same mechanisms, so this final post in the yidam series would also be a bridge into the next section, which would explain tsa lung in a naturalistic framework.

- At least, most Western historians seem to think she actually existed. I haven’t done any serious research on this. Because Buddhist history is always extensively falsified, it’s usually hard to be sure. Most of the famous people in Buddhist “history” turn out to be fictional once you dig into the texts of their supposed era. Dan Martin, one of the foremost historians of Tibetan Buddhism, points out that different sources give significantly different dates for Machig Labrdrön. Her various biographies are contradictory, and are mostly obviously mythological. Nevertheless, he accepts that she did exist. ↩

- I don’t know whether the living Karmapa is ever used as a yidam. Whether he constitutes “the same person” as his previous incarnations is complicated by the general conceptual confusions around anatman and rebirth. In any case, while there could possibly be doubts about the historicity of Machig Labrdrön, the Karmapa incarnations are as real as George Washington. ↩

- Obsession with existence and non-existence is not found in any other religion, so far as I know. My guess is that Buddhism inherited it from the Middle Eastern traditions. Between about 500 BC and 500 AD, Buddhism was in constant close cultural contact with the West, from Persia and the Middle East to Greece and Rome. See The Shape of Ancient Thought for some relevant history. ↩

- “Science” with a capital S. Pop versions of the scientific worldview take the non-existence of the supernatural, especially gods, as their essential Holy Truth. Elsewhere, I suggest that most problems atheists ascribe to supernaturalism are actually due to eternalism, and that naturalistic eternalisms are just as bad. ↩

- The book Ritual and Its Consequences: An Essay on the Limits of Sincerity insightfully explains the Scientistical, philosophical, and religious opposition to fiction, and especially mythology. I have summarized the book here (but didn’t particularly bring out its application to fiction). ↩

- See what I did there? Those three are the three kayas: dharmakaya, sambhogakaya, and nirmanakaya, respectively. ↩

- If you count eight arms, it’s because he’s having sex with his girlfriend Diptachakra. She’s the one in blue (with two arms); he’s red. ↩