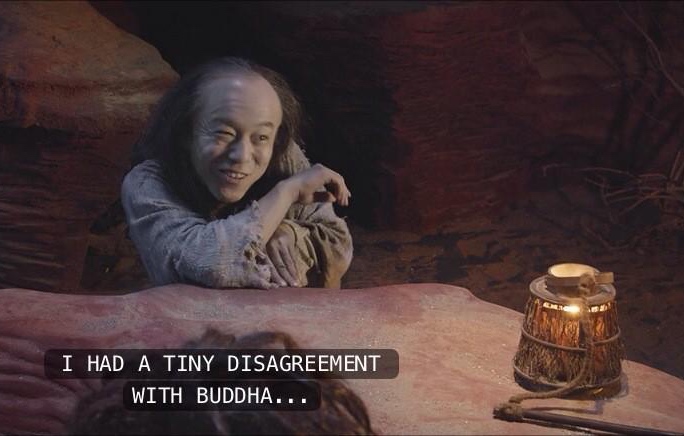

Traditional Buddhist morality is obviously wrong. But the Buddha was enlightened, and Buddhism is the correct religion; so it seems that, due to some minor mistake, the tradition does not represent the true Buddhist ethics.

Since we know what is ethically correct—and Buddha would surely agree!—we can fix it for him. That is the principle of FTFY Buddhist ethics.

[Note to future historians: “FTFY” is 2015 internet slang for “fixed that for you.”]

Current “Buddhist ethics” is identical to current Western leftish secular ethics. How can Buddhist leaders pretend that it has anything to do with Buddhism? How can traditional Buddhist moral teachings be explained away? FTFY is the main rhetorical strategy.

FTFY ethics explains what the Buddha would have said about something he didn’t discuss. For example, we can easily see that he would have approved of homosexuality. Also, he certainly would have supported intellectual property ownership.

Also, the Buddha got many things wrong, for various excusable reasons. However, we know what he should have said. For example, he surely knew slavery was wrong. However, he had to work within the constraints of the existing regime, so he had to endorse it anyway due to politics. How fortunate that we can fix that for him!

How to fix Buddhist ethics

“Compassion” is the essential tool of FTFY Buddhist ethics. “Buddhist ethics says compassionate motivation is the important thing, and we derive everything from that, so our ethics is Buddhist.” Compassion is wonderfully subjective, so you can justify anything using it—including torture and genocide, as Buddhist authorities sometimes have.

FTFY Buddhist sermons generally go like this:

- Buddhism says we should be compassionate.

- Here are some holy quotes about how important compassion is.

- Now consider this hot-button Western ethical issue: (abortion, income inequality, transphobia, GMOs, whatever).

- Clearly, the compassionate approach to this issue is [the leftish secular opinion].

- Since Buddhism is a religion of compassion, we can see that the Buddhist ethical approach to this is [the leftish secular opinion].

- Therefore, [the leftish secular opinion].

- Because Buddhism is right.

- We know it is right because [the leftish secular opinion] is compassionate, and Buddhism endorses [the leftish secular opinion], as I explained.

- Which proves that Buddhism is a religion of compassion, and therefore right.

- Here’s a Dalai Lama quote. It’s not about this issue, but you must agree he’s extremely compassionate.

This is perfectly legitimate, historically. The tradition of putting your own words in the Buddha’s mouth goes back a couple thousand years at least. But if you are going to put the whole of contemporary secular morality in his mouth, why bother?

(I’ll answer that in the next post.)

How Consensus Buddhist leaders fixed the lay precepts

Consensus “Buddhist ethics” pretends to be based on the first five lay precepts, plus the paramitas. (It ignores the other five lay precepts, and the other quasi-moral systems, and the Sigalovada.)

The paramitas are so vague that they can be safely held as theoretical ideals with little practical consequence. The precepts, however, are incompatible with contemporary American morality, so they had to be radically loosened, replaced, and/or ignored in practice.

Loosening

The following quotes are from Gil Fronsdal’s “Virtues without Rules,” about ethical teaching in the Insight Meditation Society, with some phrases omitted for concision:

[The precepts] are not to be understood as strict or absolute rules. Goldstein states: “The precepts are not taken as commandments but are followed for the effect they have on our quality of life. There is not a sense of imposition at all because they are natural expressions of a clear mind.” Kornfield insists that the precepts are “not given as absolute commandments.” And Salzberg writes, “In Buddhism morality does not mean a forced or puritanical abiding by rules,” and observes that the five precepts “are not intended to be put forth as draconian rules.”

The teachers’ insistence that the precepts are not commandments is also reflected in the seeming reluctance to apply them specifically as rules of restraint with any particularity. For example, in explaining the first precepts, Salzberg recommends the avoidance of killing. While this may be her implied intent, what she explicitly recommends is using the precept as a reflection on the “oneness of life.” In discussing the precept not to lie, she doesn’t recommend the avoidance of lying but rather the more vague “attempt not to lie.” And in discussing the fifth precept, she writes about the usefulness of temporarily “experimenting” with avoiding intoxicants. Salzberg and other teachers who explain the precepts do so mostly in general terms, focusing on principles behind them, such as non-harming and a sense of interconnection.

What’s important is not what you do (the traditional point of the precepts), but that you examine your conscience carefully, and maintain an appropriately pious attitude. “In America the precepts are generally defined in terms of intention, rather than in terms of action.”1 This is characteristic of Protestant morality.

Replacing

Since the lay precepts are contrary to Western secular morals, “Buddhist ethics” fixes them by explicit rewriting.

American teachers more often describe the positive aspect of skillful conduct, what is to be cultivated. Steven Armstrong, for instance, gives a very flexible, though inclusive, rendition of the five precepts: “a commitment to not harming,” “a commitment to sharing,” “making and keeping clear relationships,” “speaking carefully: the power of intention,” and “keeping the mind clear.”2

“Not killing” is a nice idea in theory, but:

At IMS, when issues such as a cockroach infestation arise, the teachers are not innocent of the decision to use poison… Causing an abortion is considered [traditionally] to amount to killing a human being. This formulation is consistent with the Theravādin understanding of consciousness and rebirth, but what does it mean for American laywomen trying to maintain the precepts?3

So Spirit Rock redefines the first precept as struggling to attain the correct mental attitude, the essence of Protestant ethical practice:

In undertaking this precept we acknowledge the interconnection of all beings and our respect for all life. We agree to refine our understanding of not killing and nonharming in all our actions. We seek to understand the implication of this precept in such difficult areas as abortion, euthanasia, and the killing of pets. While some of us recommend vegetarianism, and others do not, we all commit ourselves to fulfilling this precept in the spirit of reverence for life.

As for sex and drugs:

The IMS community generally gives the proscriptions against sexual misconduct and intoxicants much less scope and force than do Burmese renditions… As one teacher has put it, “Buddhists are required to avoid sexual misconduct, but it is not clear what this means in California.”4

[Traditional Burmese teacher] U Pandita does not compromise on the fifth precept.5 “Even in small amounts, intoxicating substances can make us less sensitive, more easily swayed by gross motivations of anger and greed. Some people defend the use of drugs and alcohol, saying that these substances are not so bad. On the contrary, they are very dangerous…” While I do not think that any of the senior teachers at IMS would advocate alcohol as a tool for awakening, for most of them it would be rather hypocritical to proscribe moderate social drinking as totally incompatible with dedicated practice.6

These revisions are consistent with the Protestant approach. Consensus Buddhism does not recommend renunciation (giving up all sense pleasures). Instead, it has an “ethics of mindfulness” (a rebranding of Protestant soul-searching). “Mindfulness” includes working to be satisfied with a moderate amount, simplicity, modesty, and all-around niceness.

Here’s Thich Nhat Hanh’s rewrite of the fifth precept:

Aware of the suffering caused by unmindful consumption, I vow to cultivate good health, both physical and mental, for myself, my family and my society, by practicing mindful eating, drinking, and consuming. I vow to ingest only items that preserve peace, well-being, and joy in my body, in my consciousness, and in the collective body and consciousness of my family and society. I am determined not to use alcohol or any other intoxicant, or to ingest foods or other items that contain toxins, such as certain TV programs, magazines, books, films, and conversations. I am aware that to damage my body or my consciousness with these poisons is to betray my ancestors, my parents, my society, and future generations. I will work to transform violence, fear, anger, and confusion in myself and in society by practicing a diet for myself and for society. I understand that a proper diet is crucial for self-transformation and for the transformation of society.

This is interestingly parallel to Dharmapala’s wholesale importation of then-current Western secular morality to provide “Buddhist ethical” norms for forks and buses. Healthy eating is a central commandment of current secular morality; now it’s Buddhist! The Buddha probably didn’t have an opinion about TV programs; FTFY.

Ignoring

For traditional Theravada, morality consists in submitting to an objective code of prohibitions. For the Consensus, it’s a matter of being authentic to your True Self, which is spontaneously virtuous.

Jack Kornfield:

“We use the form of rules until virtue becomes natural. Then from the wisdom of the silent mind true spontaneous virtue arises.” Elsewhere he writes, “Our actions come out of a spontaneous compassion and our innate wisdom can direct life from our heart.” The implication of the teaching that a person with spiritually developed character and insight will naturally act ethically is that, for such a person, the precepts themselves become unnecessary.7

“Trust your feelings, Luke!” Thanissaro Bikkhu, a more traditional American Theravada teacher, strongly opposes this approach. In “Romancing the Buddha,” a major influence on my understanding of modern Buddhism, he suggests that the idea derives from German Romanticism, not any Buddhist source.8

On the previous page, I wrote “few Western Buddhist teachers even attempt or pretend to live by the lay precepts.” I am not accusing them of hypocrisy in failing to live up to their chosen ethical system. I am accusing them of duplicity in pretending that the ethical system they have chosen is Buddhist.

- Jake H. Davis, Strong Roots: Liberation Teachings of Mindfulness in North America, p. 140. ↩

- Strong Roots, p. 140. ↩

- Strong Roots, pp. 140-1. ↩

- Strong Roots, p. 145. ↩

- Bikkhu Bodhi also wrote a fine article pointing out the importance of the fifth precept forbidding the drinking of any amount of alcohol. ↩

- Strong Roots, p. 146. ↩

- Quoted in “Virtues without rules,” p. 12. ↩

- Although I think he’s importantly right about Romantic influence on Consensus Buddhism, I’m not sure Romanticism is the only source of “spontaneously compassionate action.” That is a principle of Dzogchen (“lhündrüp”), and Kornfield has studied Dzogchen extensively. ↩