The method of intensification

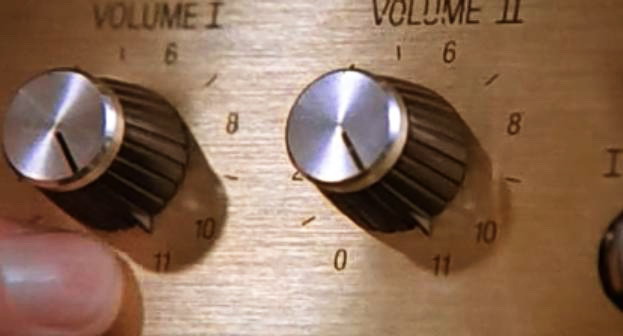

Nigel Tufnel, guitarist in the decreasingly-fictional heavy metal band Spinal Tap, explained that they could play louder than anyone else because their amplifiers went to eleven.

Tantra has a similar approach. It is not the polite Middle Way between extremes. It is the way of glorious, ridiculous excess.

Most tantric practices crank it.

Tantra has a gonzo, over-the-top attitude. Increasing passion motivates extreme action. Increasing spaciousness gives room for extreme weirdness. Increasing energy fuels extreme emotion.

Developing spaciousness

Intensification is not a goal for its own sake. Deliberately creating intensity is not natural, and extremes have no particular value.

Instead, this is a method: an exercise, an aspect of the path. It prepares you for the culmination of tantra—fluid, effective action—by developing spaciousness.

Sutra (mainstream Buddhism) develops spaciousness in almost exactly the opposite way: through self-restraint. This is also a valuable method, and also not particularly natural; there’s nothing particularly enlightened about self-restraint itself.

It’s funny that sutra and tantra take opposite approaches to developing spaciousness—and they both work! You can use both methods—although not at the same time. With practice, you learn which is the best approach for you in particular situations.

Intensity builds capacity

Tantra is extreme because reality is extreme. One way or another, you are going to have to deal with sex, love, loss, conflict, failure, and our good friends “old age, sickness, and death.”

Sutra recommends that you minimize your exposure to such emotionally provocative situations. It recommends that you develop equanimity to meet them without passion when you cannot avoid them.

Tantra recommends that you gradually increase your ability to act effectively in extreme situations, by developing spaciousness and passion together. You can do that relatively safely by deliberately creating intensity, in a controlled situation. There you practice meeting strong feelings with accommodating space.

Intensity incinerates meaning

“Spaciousness” means letting go of the compulsion to make experiences mean something. Those meanings are mostly created conceptually.

Sufficient intensity actually overwhelms your ability to conceptualize. When you stub your toe, for a couple of seconds there is no thought; there is only pain. Or, you can be so angry, or so turned on sexually, that you can’t think. Usually this is considered a problem, but for tantra, it is an opportunity to experience reality without your concepts getting in the way.

Any intensity will do

Tantra contains endless methods for generating different intense experiences. Many of these are elaborate and technical. I think that’s unnecessary. What matters is an understanding of the principle of all these methods: you deliberately intensify experience, and commit to joining that with space.

It doesn’t matter what experience you intensify. Early tantra mostly used sexual pleasure. That is inherently intense, and has the happy byproduct of being enjoyable. Pain is just as good, and may be easier to arrange. It’s used a lot in Hindu tantra, but much less in Buddhism. You can use intense anxiety or desire or even boredom.

Recent Tibetan tantra makes extensive use of paranoia. The lama creates intense paranoia among his or her students, over totally trivial issues. The advantage here is that—because nothing real is at stake—it’s safer than working with rage or lust.

It’s pretty unpleasant, though. Also, inevitably, not all the paranoia gets successfully transformed into constructive activity. As a result, there is a strong undercurrent of paranoia throughout Tibetan Buddhism. This can be quite ugly and problematic; I’ll discuss that when I write about Tibetan politics.

Over-the-topness

Tantra promotes outrageousness—not from violating norms for their own sake, but because deliberate intensification is not normal, and takes you places most people never go.

The outrageousness of tantra is related to, but different from, the outrageousness of the 20th century bohemian artist. It shares a willingness to go into creative madness, and to accept terror and revulsion.

The slogan of the romantic rebel is épater le bourgeoisie: “let’s scandalize the middle-class squares!” This is aggressive and smug; the attitude is “we’re better than them because we can tolerate more weirdness.” That comparison is quite unnecessary.

Usually, tantra is outrageous in order to explode the limited conceptions of tantric practitioners themselves—not for the effect it has on other people. Occasionally it’s useful to shock the public, but only if that leads to some genuine benefit.

Going too far

In tantra, you may take it way too far, until it breaks. (Whatever “it” is.)

If it breaks, the breach reveals the underlying structure of experience, in the manner of breaking. Conceptual mind smoothes over the grittiness of experience, so long it is able to cope. When coping fails, you can see the machinery grinding away beneath that.

If you can maintain some spaciousness through the breakdown, what it reveals is likely to be very funny.

Big and stupid

Tantra is big and stupid. It’s like a wildly enthusiastic but not very bright St. Bernard puppy.

Sometimes it’s good to be stupid. It’s endearing, and it cuts through intellectual complexity that may just be a psychological defense against experiencing the rawness of reality.

But the amped-up stupidity of tantra can get tiring, tiresome, and stale—like heavy metal.

In that case, you might want to try Dzogchen, which is approximately tantra minus the big and stupid. I’ll say more about that later.