According to Western psychology, “flow” is a mental state that occurs when you are totally immersed in an activity that consumes your full attention and skill. It’s described by athletes as being “in the zone,” and by musicians as being “in the groove.” It’s highly enjoyable; often the best thing in life.

Psychological flow is closely related to Buddhist Tantra, which is also about free-flowing energy. But there are important differences. Here I want to use those similarities and differences to begin to explain the “path” aspect, or methods, of tantra.

Let me jump ahead to my punchline. Flow depends on highly-controlled conditions, so it is frustratingly elusive. Tantra has no conditions, and so can be practiced under any circumstances, including complete chaos. Flow lacks both spaciousness and passion, which are the keys to tantra.

On my previous page, I tried to make tantra sound disappointingly ordinary. Here, understanding how tantra relates to flow might get you excited about it again—on a more realistic basis.

Flow: The psychology of optimal experience

“Flow” was made famous by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s breakthrough book Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. It introduced his scientific studies on the flow experience, and on enjoying life, to a general reading audience. This was the most important early work in positive psychology and happiness research.

I suspect that this book has had a major influence on modern Western Buddhisms, especially the “mindfulness” varieties. Most of what the book has to say is compatible with Buddhism, and usefully complementary to it. It has many useful ideas about how to live a satisfying and productive life.

It is somewhat dated (published 1990) and problematic; but I still recommend it highly. It’s at least worth reading the first four chapters, which summarize Csikszentmihalyi’s research. (After that he starts to get philosophical, goes far beyond his data, and tries to make flow into a General Theory of Everything.)

How flow and tantra are similar

Enjoyment

Flow research began with the question: what makes for long-term happiness? The answer was: enjoying everyday life; and psychologists found that enjoyment is best provided by flow experiences. Apparently, the more flow people experience, the more likely they are to say they are satisfied with life. This was the first of two major results of Csikszentmihalyi’s research.

Enjoyment is not the same thing as pleasure (which is one reason hedonism doesn’t work). Enjoyment requires attention and active involvement, and has a transformative effect on the personality. Sense pleasure, by itself, does not; and according to the research, it doesn’t lead to happiness. (It is helpful, though, because it’s easier to enjoy pleasure than pain.)

Enjoyment is also central to tantra, where it also is considered to transform your personality. In tantra, enjoyment is only a tool, though; in positive psychology, it is an ultimate goal.

Attention and energy

The flow research, like tantra, concerns non-mystical “energy.” Energy is what flows smoothly in the flow state.

Csikszentmihalyi found a close connection between energy and attention. Flow occurs when attention is closely controlled. The activities that typically produce control are those that demand highly-practiced, intense concentration of attention.

Tantra produces enjoyment through attention control practices. Tantra directs and manipulates energy through visualization and physical yogas. Unblocking energy flow is, in fact, its essential method.

Details and perception

Research found that flow depends on total involvement with the details of a situation. This requires skilled perception. Tantra is also all about total involvement and developing perception.

Time consciousness

In the flow experience, you are totally “in the moment,” and your perception of time may change radically. It may speed up or slow down. Tantra is also about now, and has methods specifically for altering your perception of time to force you into nowness.

Loss of self

In flow, commonly you lose your self. Activity becomes spontaneous, almost automatic; you stop being aware of yourself as separate from the action. Musicians report that “the music plays itself.” Footballers feel their body as part of a joint organism, the team, which acts as one. In sex, you may lose track of whose body is whose.

This is, of course, a common theme in all of Buddhism. Psychology sees loss of self as a temporary illusion, though; whereas Buddhism sees the self as a temporary illusion.

Mastery and power

Flow both requires, and helps produce, mastery of skills. It leads to a sense of power and control. Ultimately, according to Csikszentmihalyi, it results in “extraordinary individuals.”

Csikszentmihalyi sees social conditioning as a major obstacle to life fulfillment. He writes that “the most important step in emancipating oneself from social control is the ability to find rewards in the events of each moment” (p. 19).

All this is also true for tantra. I’ll discuss mastery, power, and freedom in depth, in the “result” section of my introduction to tantra. (That’s coming up, half a dozen web pages from now.)

Flow-producing activities

The activities most likely to produce flow are athletics (Csikszentmihalyi discusses particularly yoga and martial arts); artistic performance (such as music and dance); sex; play; and ritual.

These are all specifically used and elaborated in Buddhist tantra.

Flow, ritual, and religion

Flow and religion have been intimately connected from earliest times. Many of the optimal experiences of mankind have taken place in the context of religious rituals. Not only art but drama, music and dance had their origins in what we now would call “religious” settings. (p. 76)

[Flow provides] a sense of discovery, a creative feeling of transporting the person into a new reality… [It leads] to previously undreamed-of states of consciousness. (p. 74)

Ritual is a highly-practiced, creative performance, which demands total concentration and sensory involvement, while channeling intense energy. That makes it an ideal flow-producing activity.

Not surprisingly, tantra is known as the branch of Buddhism most concerned with ritual…

The conditions of flow

The second major result of the flow research is a series of conditions that are required to produce the flow experience:

- A task that you are reasonably likely to succeed at

- Difficult enough to demand total attention

- With clear rules and goals

- Immediate feedback

- And an absence of distractions, so you are able to concentrate

(As I’ll explain below, tantra does not share these conditions—so this is the point at which we begin to see how tantra and flow differ.)

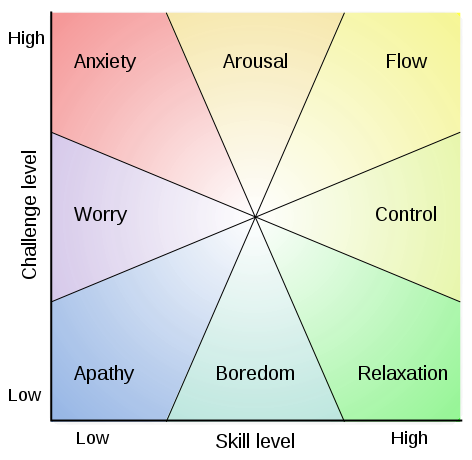

Flow happens when you are operating just inside the boundary of your ability. There must be a near-perfect balance of the task’s challenge and your skill. Csikszentmihalyi describes this as the “flow channel” of not too hard and not too easy. It is the upper right sector in this diagram:

In the flow channel, the action goes smoothly, and you feel like you are in control, yet it is demanding enough that you have to shut out all distractions. You do not have enough energy left over to indulge in self-concern or worries. You have to be in the present, letting past and future drop away.

Flow produces mastery because it motivates you to develop a skill. As you get better at it, you have to take on increasing challenges to stay in the groove.

Video games and flow

Video games are designed to produce flow, which is what makes them enjoyable. They are engineered with clear rules and easy-to-understand goals, and give immediate feedback (such as a score or damage bar). They present a long series of carefully calibrated, increasing challenges, with skills to develop. They demand intense attention control, as you have to keep track of numerous monsters and constantly scan the screen for threats and opportunities.

The limitations of flow

There’s a serious problem. Life mostly does not meet the conditions required for flow. The world is largely chaotic, undefined, jerky and unpredictable. For that reason, flow can be frustratingly elusive. Flow requires “order in consciousness” (p. 6).

To a limited extent, it is possible to rearrange your mind and your life to be smoother and more orderly, so flow occurs more often. To a limited extent, that is a good idea.

You might choose to spend as much time playing video games as possible. That’s likely to maximize flow.

I enjoy video games; and at their best, I think they can be high art, and deeply meaningful.

However, even if it were possible to arrange my life so that I could play outstanding video games all day, every day, immersed in flow—I would not want to do that. It would seem trivial and self-indulgent. There are things I value far more than enjoyment.

It would also seem like evading a responsibility to reality. “Games,” writes Csikszentmihalyi, “enhance action and concentration during ‘free time,’ when cultural instructions offer little guidance, and a person’s attention threatens to wander into the uncharted realms of chaos” (p. 81).

But this is just the point: the “uncharted realms of chaos” are what I find most interesting and important.

In tantric terms, this is “emptiness.” Excessive indulgence in entertainment staves off awareness of emptiness with triviality.

“In normal life,” says Csikszentmihalyi, “we keep interrupting what we do with doubts and questions… but in flow there is no need to reflect, because the action carries us forward as if by magic” (p. 54).

The questions posed by emptiness are central to tantra. Curiosity is one of tantra’s highest values. The courage to face up to unpleasant realities is another.

Tantra is not limited by conditions

Tantra is spacious passion. Spaciousness is tolerance of chaos, unpredictability, discontinuity and nebulosity.

Flow excludes most passions. It can produce drive and exhilaration; but any other strong feelings are likely to disrupt it. Tantra can work with any, and all, emotions.

Flow depends on narrowed, intensely-focused attention. Tantra is compatible with (and sometimes requires) panoramic awareness.

Tantra is a way of living that applies in all circumstances. Tantra says that it is possible to enjoy anything, without any conditions.

The flow research is useful, however, in explaining how and why the tantric methods work. They produce deliberately and directly many of the same effects that occur in flow activities only accidentally. Loss of self, nowness, attention control, unclogging energy—these are the specific goals of specific tantric practices. You could play a lot of football before stumbling on them occasionally.

I hope this is starting to sound intriguing…

The meaning of life

Csikszentmihalyi recognized the problem I’ve pointed out. Ideally, he says, we’d like all of life to be flow; but chaos makes that difficult at best. And, there are values in life beyond enjoyment.

The last chapters of his book attempt to address these limitations. Here he goes far beyond his psychological research, into philosophy, where he flounders, unqualified.

His answer is that you must find a single unified life purpose; this makes it possible to make everything into a continuous flow activity, because all tasks are subordinated to that one goal.

He draws on existentialism and on psychoanalysis:

- Since Nietzsche, he says, we understand that life has no inherent meaning. However, life can—and must—be given an overarching meaning by each individual. This is the existentialist answer to all problems.

- A single, individually-chosen goal integrates the self by bringing all personal faculties under unitary control of the ego. This is the psychoanalytic answer to all problems.

Existentialism and psychoanalysis were the last, dying gasps of “modernism”: the quest to find a solid foundation for meaning.

Both, in my opinion, were utter failures; and this is now widely recognized. (I’ve written about that here and here and here, for instance.)

Buddhism after modernity

Spaciousness is being comfortable with meaninglessness. Passion is the spontaneous arising of meaning from empty space.

Tantric Buddhism, I hope and believe, offers resources for living after modernity—after we have abandoned the futile search for stability, unity, certainty, order, and ultimate meanings.

Much more about that later in this series.